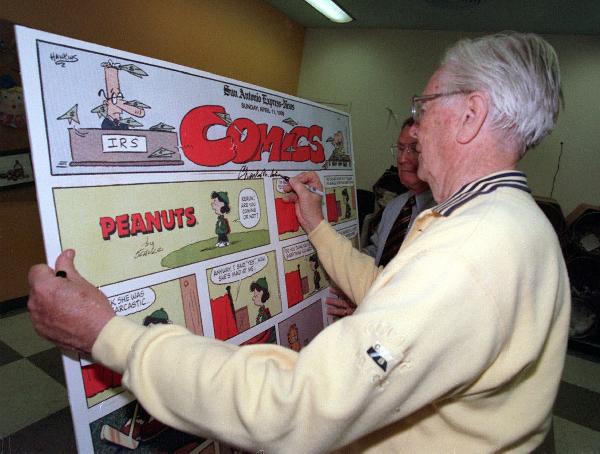

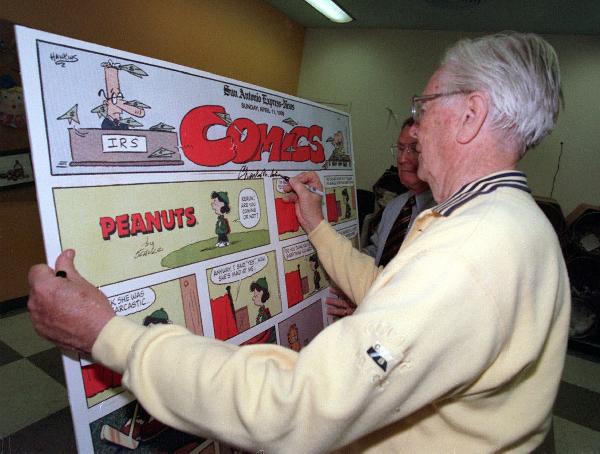

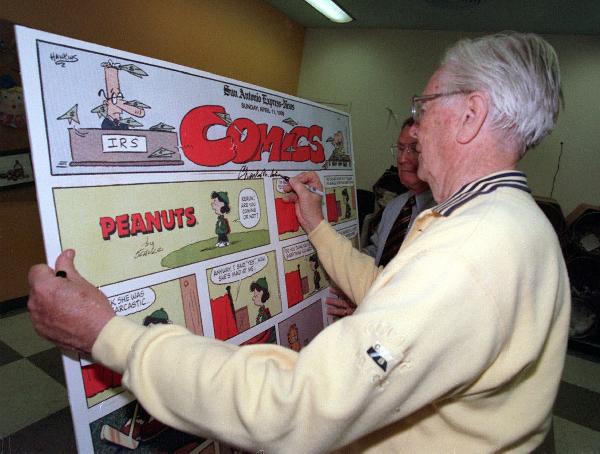

Charles Schulz signs a copy of his Peanuts comic strip May 6, 1999, at the National Cartoonist Society's 53rd annual Reuben Awards weekend in San Antonio, Texas. (Associated Press photo/Morris Goen)

And responds...(page 11)...

More news from the media world...

Schulz says he did not realize the popularity of his strip

February 10, 2000

The Associated Press

SANTA ROSA, California -- "Peanuts" creator Charles Schulz says he had no idea how many lives he had touched until he announced his retirement and was inundated with adulation.

The 77-year-old cartoonist, who has been selectively granting interviews since he announced his retirement in December, talked Wednesday with the KSRO radio in Santa Rosa, where he lives and works.

Schulz was diagnosed with colon cancer and suffered a series of small strokes during emergency abdominal surgery in November. He said he can't see well from the left side and has difficulty speaking.

As a result, he said, he doesn't expect to draw again.

"All of a sudden, one day, it's taken. It's gone. I can't do it," he said.

Schulz drew "Peanuts" for nearly 50 years. His last new daily strip ran Jan. 3. His final new Sunday strip runs this Sunday.

Schulz said he's not bothered that the tributes that have followed the news of his retirement are the sort that are typically reserved for someone's eulogy.

"I'm pleased that I was able to live long enough to see it all," he said.

Faith in the funny pages

February 10, 2000

By Sara Foss

Scripps Howard News Service

"If Jesus had owned a dog, what kind do you suppose it would have been?" Charlie Brown once pondered in a "Peanuts" comic strip, prompting Snoopy to note, "If he had a dog, all of the apostles would have wanted one."

An unlikely source of spiritual wisdom, the funny pages have long explored faith and spirituality, and Charles Schulz's strip has been perhaps the most delightful visitor into these territories.

But even after the final new "Peanuts" strip appears in newspapers across the country Sunday, comic strip readers will continue to receive spiritual instruction -- whether they know it or not.

Comics and other artistic mediums provide easy-to-understand messages of morality, much the way parables did for Jesus, theologian Robert L. Short explained in his 1965 book, "The Gospel According to Peanuts."

"The Church will always need `fresh' parables -- whatever their original `intent' -- in which to pour the `new wine' of the New Testament," Short wrote.

Short's book, which is being reissued for a 35th anniversary edition, in some ways resembles a children's book, with its plethora of cartoons. But the text is a serious rumination on Christianity, with references to difficult philosophers such as Paul Tillich and Soren Kierkegaard. The new edition will arrive at local bookstores this month.

Although "Peanuts" characters frequently allude to the Bible -- a discussion of the Book of Job once broke out at Charlie Brown's pitching mound -- no direct religious reference is necessary for a religious message to be given.

For example, Short describes the "Peanuts" gang as representations of original sin, who cling to idols rather than worshipping God. Linus' attachment to his blanket, Short wrote, is one such example of idolatrous faith.

Short also has talked on the theological implications of "Calvin and Hobbes" and of Dr. Seuss books, but he said Schulz is the best at bringing religion into comics.

"He has that kind of background," Short said. "When you walk into his library at home, it looks like a minister's office. The shelves are full of books."

Raised Lutheran, Schulz is active with the Church of God based in Anderson, Indiana, and lives in Santa Rosa, California. Schulz, who recently underwent chemotherapy for colon cancer, was unavailable for an interview. His illness caused him to retire in December.

Schulz's religious references didn't sit well with all readers.

"I believe it is inexcusably poor taste, and offensive to many readers both Christian and Jewish, to use texts from and reference to the Bible...especially in a comic strip," one reader wrote to Schulz in 1969. The letter is included in "Peanuts: A Golden Celebration," a collection of comics by Schulz.

But some people offered praise.

Like Schulz, "Family Circus" creator Bil Keane, 77, said he used to get an occasional complaint about using religion in his strip.

"Now those same people write me to say, `Thank you for putting spirituality into the comics page,' " he said.

Keane often spins gags out of children saying prayers or the family attending church. In one, young Jeffy prays, "Our Father, who art in heaven, how did you know my name?"

Keane's depiction of the family's grandfather sitting angelically on a cloud in heaven, listening to his grandchildren, is among his most popular images. Readers use the strip to show their own children where people go after they die.

"To see that in a comic strip, it does more than 10 homilies by a priest," said Keane, a Catholic, from his home outside of Phoenix.

"I never set out to be an evangelist," he added. "All I'm doing is showing the way religion touches a child's life or family life."

Priests and ministers sometimes use the work of Chris Browne, who draws "Hagar the Horrible," in their sermons.

"I love that," Browne said via cell phone outside his dentist's office in Sarasota, Florida.

Like "Peanuts," Hagar sometimes features biblical quotes. In one strip, a clergy member preaches, "And the Lord said, `Be fruitful and multiply.' " From his seat, Hagar remarks, "You said there wasn't going to be any math!"

Browne's father, Dik Browne, who died in 1989, created "Hagar." A history buff, he selected the Viking period as a setting for the strip because it was a dynamic time, when Christianity was beginning to spread through Norway and Sweden. "The drama of that attracted my father," Browne said.

Browne, 47, described himself and his parents as Catholic believers who don't attend church on a regular basis. His father illustrated books and a television show for Bishop Fulton J. Sheen, a popular Catholic personality in the 1950s and '60s.

One cartoonist who has received national attention for his use of religion is Johnny Hart, who draws the prehistoric "B.C." While Hart said a number of newspapers have dropped "B.C." strips with Christian themes, several papers that were contacted gave different reasons for not running certain comics.

The Los Angeles Times alternates its strips, and so not every "B.C." cartoon is printed, said Nancy Tew, comics editor.

In 1996, the Times chose not to print a "B.C." cartoon drawn for Palm Sunday because of its Christian theme. In the strip, caveman Wiley talks about the Christian belief that Jesus atoned for the sins of the world through his crucifixion on the cross.

The Times ran the strip on the religion page following protests from readers. Objections to the Times' decision were voiced by evangelist Pat Robertson on his show "The 700 Club" and the Christian Coalition, a national political action organization founded by him.

At the time, Times editors explained that in the past they had printed some "B.C." cartoons with religious themes, but pulled comics they viewed as containing religious content that was inappropriate for the funny pages.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution dropped "B.C." altogether, though one editor says it's not because the strip is too religious. According to Frank Rizzo, comics editor at the Journal-Constitution, the paper dropped the strip because they felt "B.C." was past its prime. "If it was just because of religious references, we'd have to drop `Peanuts,' `The Family Circus' and `Dennis the Menace,' " Rizzo said.

Hart, 69, said he works religion into the strip on religious days, just as he'll do something patriotic on Independence Day.

"The Bible tells me about the great commission to go out into the world and teach the gospel to every creature," Hart said. "I'm following what I as a Christian am instructed to do, what I was given a gift to do, and a platform."

The work of some cartoonists contains a message of religious tolerance rather than a Christian theme. Wiley Miller said that in his strip, "Non Sequitor," the subject of religion comes up, but "it's more of a civil rights thing."

"I don't proselytize," Miller, 48, said from his studio in Iowa City, Iowa. "I don't hold one religion over another."

Sometimes Miller uses religious images, such as the pope and the fires of hell, as sight gags. In one strip, a man shoveling snow is jealous of his neighbor, who has a Moses-like ability to part drifts of snow by holding his palms outward.

In his new book of cartoons, "Beastly Things," one section includes religious cartoons. Raised Catholic, Miller said he no longer considers himself a member of any organized religion.

A subtle touch is needed to mix humor and religious messages, said Amy Lago, who served as Schulz's editor for 11-1/2 years at United Media, a division of E.W. Scripps Co., which also owns Scripps Howard News Service.

"I don't think religion is something he wanted to bring out in a preachy way," Lago said. "It's part and parcel of his life. Any good cartoonist uses their life to create strips."

Lago recalls that she did discuss the whether-Jesus-had-a-dog strips with Schulz and has formed an opinion of her own.

Of course, Jesus had a dog, she said, because "all good people have dogs."

How Schulz's Charlie Brown Became a Big Hit -- on TV

The popular comic strip, which concludes Sunday, first made it onto the small screen in 1965 and has been seen every

year since. But it wasn't a sure thing, and it wasn't easy.

February 11, 2000

By CHARLES SOLOMON

The Los Angeles Times

Charlie Brown -- the star of Charles Schulz's "Peanuts" comic strip, which will have its last original run in newspapers around the

world on Sunday -- was always a problem for television. Big head, little feet, simple animation style and a sidekick who thought in

broad, often literary terms but only uttered a "bark" here and there.

While cartoonists and commentators have paid tribute to Schulz's work as a print cartoonist, as CBS will tonight in a special

"Good Grief, Charlie Brown: A Tribute to Charles Schulz," what has generally been overlooked is the impact of "Peanuts" on

television animation.

When "A Charlie Brown Christmas" premiered on CBS on Dec. 9, 1965 -- it has been rerun every year since -- network

executives were worried that viewers wouldn't show up. They did, with the show commanding a 47 share, which meant nearly half the

TV sets in the country were tuned in.

Viewers approved, and critics soon weighed in too, hailing it a Yuletide classic.

Yet the first "Peanuts" special had an unlikely journey from concept to the small screen. In reality, "Charlie Brown Christmas"

was a hastily made experiment that was initially regarded as a failure by its creators.

The origins of the show go back to 1963, when independent film producer Lee Mendelson decided to follow his documentary

about Willie Mays with a film about Schulz. Mendelson, who is serving as executive producer with Rand Morrison on the CBS

tribute, felt the strips on Schulz's drawing board were too static and suggested adding short animated sequences. Schulz agreed and

asked his friend Bill Melendez, who had directed the "Peanuts" commercials for the Ford Falcon in 1957, to do the animation.

Mendelson made "A Day in the Life of Charles M. Schulz" on spec. Over the next year, he took it to all three networks and more

than 20 advertising agencies: No one would buy it. But in May 1965, John Allen of the McCann-Erickson agency contacted

Mendelson and Schulz. Coca-Cola was looking for a special.

Could they could do an animated "Peanuts" Christmas show?

The two men hastily prepared a rough scenario; a few days later, they received a telegram confirming its sale and work on "A

Charlie Brown Christmas" began.

Television's first fully animated special had been a 15-minute adaptation of Stravinsky's ballet "Petroushka," which appeared as a

segment of "The Music Hour" on NBC in 1956. More typical were the one-hour versions of children's stories produced during the

mid-'60s, such as "Return to Oz" and "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer," or the TV retelling of "A Christmas Carol" starring Mr.

Magoo (1962).

Schulz and Mendelson felt they could tell a better story if the "Peanuts" special were only a half-hour. Melendez agreed, knowing

it would be impossible to produce an hour's worth of animation on such a short schedule anyway. CBS, McCann-Erickson and

Coca-Cola agreed to the shorter length.

"I didn't know what to charge," recalls Melendez, who as a successful commercial director had never budgeted a film longer

than 60 seconds. "They told me they'd give me top dollar -- what they gave Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera. I said, 'They're not going to

make the picture -- you want them to set the budget?' " But it was a take-it-or-leave-it deal, which he took, getting paid about $76,000

to make the special, which ended up costing him closer to $96,000.

In retrospect, Melendez feels "those dumb budgets" helped them make a better film. It forced the invention of a limited style of

movement that fit Schulz's minimal drawings.

"Charlie Brown has a big head, a little body and little feet; he can't walk the way a normal human would," Melendez explains.

"After several experiments, I decided, because of their size, these kids would take a step every six frames, or four steps a second:

click-click-click-click. If we had tried to move them in full, Disney-style animation, it would have been a disaster."

In another break with tradition, the artists used children for the characters' voices, rather than adult actors. The children were

mostly nonprofessionals, and some of them were too young to read their parts -- leaving Melendez to read the lines and have the children

repeat them.

Snoopy posed a special problem. In the strip, he never spoke, but he thought in words. Melendez planned to use an actor to

verbalize Snoopy's thoughts, but Schulz vetoed the idea, saying, "Nope, he's a dog and he doesn't speak. He barks, he thinks, but

he doesn't speak English."

Melendez recorded himself doing various sounds and speeding them up, trying to find something that sounded like a dog's bark at

the same time it communicated Snoopy's feelings. He planned to have an actor redo the noises, but the sound editors used his

temporary track when time grew short. Everyone liked the results, and Melendez has supplied Snoopy's "voice" ever since.

The "Peanuts" artists chose jazz musician Vince Guaraldi, whom Mendelson found with the help of a San Francisco critic, to provide

the score. Guaraldi's upbeat tunes suited the simple animation and gave the program a strong musical identity.

The most famous moment in "A Charlie Brown Christmas" comes when a discouraged Charlie Brown asks, "Isn't there any

who knows what Christmas is all about?" Linus says he does and recites the Gospel According to St. Luke. Melendez remembers he

was shocked when he came to that scene in the script: "I said, 'Sparky [Schulz's nickname], we can't have that -- this is religion, it

just doesn't go in a cartoon.' He just looked at me very coldly with his blue eyes and said, 'If we don't do it, who will? We can do it.'

And he was right."

Mendelson recalls that when he showed the special to two CBS vice presidents, "they didn't try to hide their disappointment. 'Too

slow . . . the kids don't sound pro . . . the music all wrong . . . the Bible thing scares us . . .' "I thought we had killed it," adds

Melendez.

They hadn't. "A Charlie Brown Christmas" drew a 47 share when it premiered in 1965, and a 57 share when it was rerun the

next year. It also won an Emmy and a Peabody Award.

The success of "A Charlie Brown Christmas" made the half-hour format the standard for animation for the next 35 years,

and set the pattern for prime-time adaptations of comic strips, including "Garfield" and "Cathy."

Looking back at that first, uncertain attempt to bring Charles Schulz's world to television, Melendez concludes, "We caricatured

life very much in the way that the strip did. And what made the strip so incredibly popular was that it was a caricature of life, but in a

very human fashion."

Linus Pays Tribute To a Good Man -- Charles Schulz

Kenwood character recalls early days with pal Sparky

February 11, 2000

Bill English

The San Francisco Chronicle

For Linus Maurer, the announcement by Santa

Rosa cartoonist Charles M. Schulz that the last new

Peanuts strip will run on Sunday means more than

just the loss of a favorite comic strip. It's the end of

a personal era; the departure of a cartoon alter ego.

Fifty years ago, Kenwood resident Maurer, 73, met

Schulz at Art Instruction Schools Inc., in Minneapolis,

where both men were cartoon instructors. At the

time, the Peanuts strip was just getting off the

ground and heading into syndication.

Schulz, 77, announced in December that he was

retiring because of colon cancer. In his new book

"Peanuts: A Golden Celebration" (Harper, $45),

he writes: "Linus came from a drawing that I made

one day of a face almost like the one he now has. I

experimented with some wild hair, and showed the

sketch to a friend of mine who sat near me at art

instruction, whose name was Linus Maurer. It

seemed appropriate that I should name the

character Linus."

Lucy's younger brother had entered the frame. The

rest is cartoon history.

CARTOON LIFE

Like Schulz, Maurer has also enjoyed a long and

successful career as the creator of syndicated

newspaper features. After he graduated from the

Minneapolis School of Art in 1950, he created such

popular cartoon strips as Old Harrigan,

Abracadabra and In the Beginning. Maurer writes

the internationally syndicated numbers puzzle

Challenger for King Features, which appears daily

in The Chronicle. He also draws and writes

Newshound, a twice-weekly editorial cartoon for

the Sonoma Index-Tribune.

"When I first arrived at Art Instruction, Schulz and

a guy named Charlie Brown were already working

there," Maurer says. "At the time, none of us had

any way of knowing how successful the Peanuts

strip would eventually become. But I had the good

fortune to be sitting right next to Sparky and got a

chance to watch him develop some of the

characters. That was a lot of fun."

Those early drawings proved to be the genesis for

one of the most important traditions in American

cartoon culture. The phenomenal influence of

Peanuts has been duly noted by many other modern

cartoonists, including Doonesbury's Garry Trudeau,

who wrote in the Washington Post: "Peanuts is the

first and still the best postmodern comic strip."

Indeed, no cartoon strip in history can match

Schulz's worldwide audience. With 355 million

readers in 2,600 newspapers, the strip is read in 75

countries.

Linus isn't shy about laying on the accolades for his

old friend and colleague.

"I believe Charles Schulz has had more of an

impact on the world than any other writer in

history," Maurer says. "I'm sure he reaches more

people than Shakespeare ever did. He's been read

every day by people all over the globe for 50 years.

What other entertainer has had that kind of

audience?"

END OF AN ERA

Maurer feels his Schulz will be impossible to

replace. Unlike some cartoonists, he wrote and

drew every line of his over 18,000 strips during his

lengthy career. Maurer has a great respect for his

colleague's dedication to his craft.

"When you write and draw a cartoon, you don't

want anyone else doing the creative work for you,"

Maurer says. "Do you think Ernest Hemingway

would let someone else write a chapter of one of his

novels just because he was feeling tired? It's not just

about drawing -- it's about thinking. It's about the

ideas that go into the cartoons. You've got to do it

all yourself."

Schulz has stipulated that no one will write or draw

Peanuts after he retires. Maurer feels there was

never any danger of someone replacing the

legendary cartoonist.

"Nothing can ever replace or duplicate the Peanuts

strip," Maurer says. "When it first came out in the

early '50s, it was a departure from things like Dick

Tracy and Lil' Abner. The Peanuts strip dealt with

satirical commentary and human relationships."

But it wasn't an immediate success. In the beginning,

the new concept was not universally understood or

accepted.

"I remember a little while after Peanuts came out, I

created a strip called Old Harrigan," Maurer recalls.

"One editor told me he loved the drawings, but he

didn't think you could put adult humor in the mouths

of children. This guy said Peanuts would never last.

I did Old Harrigan for five years before I went on to

work in television."

Maurer believes the miniature world Schulz created

will be sorely missed.

"All this time, Sparky has been putting on a

continual stage play for us," Maurer says. "He

creates all the characters. He writes the stories and

does the costumes. He directs the action and

produces the whole thing. Peanuts was his life's

work. When he stepped to the drawing board, he

invented a whole new world. And he shared that

world with his readers. If he hadn't gotten sick, I

don't think he would have retired. The strip was

such an important part of his life. It was an

important part of all of our lives."

FOREVER LINUS

For most of his adult life, Maurer has felt the impact

of being a cartoon icon, and it doesn't take much of

an imagination to see him as a walking, talking

Peanuts prototype.

"I feel very honored that Schulz used my name in

his strip," Maurer says. "I can't imagine what my

life would have been like if the cartoon Linus had

never existed. I think we have a lot in common.

We're both philosophical and level-headed."

But does the real Linus have a security blanket?

"No," Maurer says, "but I do keep a lot of

sweaters and jackets in the trunk of my car."

Maurer has no plans for retirement himself. Over

the past few years, his lifelong passion for painting

has blossomed into a thriving career. His colorful,

almost Pop Art paintings, featuring busty women

with lavish thighs, have recently been used on the

covers of Sonoma Business Magazine and will be

seen on wine labels in the near future.

"I love to paint people in happy situations like

weddings and wine tasting events," Linus says. "I

like to paint big bodies and tiny heads, because that

lends itself to good composition.."

When Maurer is asked to offer advice to anyone

interested in getting into the cartoon game, he

speaks with the authority of a teacher and seasoned

professional.

"You've got to learn to think and write funny,"

Linus says. "You can be the best illustrator in the

world and not make it as a cartoonist. It's a very

specialized form of art. A simple way of looking at

the world. That's why Peanuts was so successful for

so many years. It's a very clear expression."

But will Charlie Brown and his friends be

remembered in a thousand years?

"I personally will remember them for the next thousand years," Linus

says with a smile. "And I think if the rest of the

world stays well, they'll remember them too."

Peanuts sculpture proposal drawn up

February 12, 2000

By MIKE MCCOY

Santa Rosa Press Democrat

Charlie Brown and his dog Snoopy, who

have called the funny pages home for five

decades, could soon find a new place to

live in Santa Rosa's Depot Park.

Santa Rosa city officials are considering

spending $168,000 for a life-sized

sculpture of the comic characters to honor

Peanuts cartoonist and Santa Rosa

resident Charles Schulz.

Schulz, whose 50 years of drawing the

Peanuts strip ends Sunday, is turning his

full attention to a battle with colon cancer.

The bronze sculpture will feature Snoopy

standing beside a 4-foot-tall Charlie

Brown. A contract for the artwork will go

before the City Council on March 7.

Depot Park is part of Santa Rosa's Old

Railroad Square.

The sculpture will be enclosed by a railing

decorated with a half-dozen Peanuts

scenes and characters. The railing will

discourage vandalism, according to the

city.

Mayor Janet Condron said the $168,000

price tag is a bargain for a sculpture by

artist Stan Pawlowski of Long Beach. He

usually charges $250,000 for such a piece,

according to a city report.

"(Pawlowski) has been translating Mr.

Schulz' characters into three-dimensional

art for over 20 years,'' said Pat Fruiht, the

city's community affairs director. "He is

someone Mr. Schulz has worked with and

has confidence in.''

Fruiht said the city hopes to unveil the

artwork next Oct. 2, the anniversary of the

date when his first strip ran 50 years ago.

It now appears in more than 2,600

newspapers and 75 countries.

The city has been engaged in discussions

about how to honor the ailing Schulz as he

celebrates his half-century of work.

Condron said in her talks with the Schulz'

family, "the sculpture is the thing he seems

most interested in.'' She said Schulz has

rejected proposals to rename a street for

him or build a fountain in his honor.

Fruiht said the sculpture's location in the

heart of Railroad Square also met with

Schulz' approval.

Fruiht said it is the perfect spot since it will

be near the Santa Rosa Convention &

Visitors Bureau.

"A lot of people come to Santa Rosa

because of Mr. Schulz, particularly

because of his Redwood Ice Arena, and

that attraction will be even greater once his

museum is built,'' Fruiht said.

Schulz plans to have a 17,000-square-foot

museum built next to the ice arena to

display his work.

"Having it (the sculpture) near the

convention and visitors bureau, where a lot

of tourists come for information, makes a

lot of sense,'' she said.

Final "Peanuts" Comic Says Goodbye

February 12, 2000

The Associated Press

SANTA ROSA, California -- Good Grief! It's the final

goodbye for Charlie Brown and his pals.

Charles Schulz ended his 49-year-old "Peanuts" comic

strip with a poignant letter published in Sunday

newspapers across the country. The signed letter also

ran when he ended his daily comic strip on Jan. 3.

The 77-year-old cartoonist -- beloved for his timeless

characters Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Linus and Lucy -- is

retiring to turn his full attention to fighting cancer.

In several Sunday newspapers, the strip opens with

Charlie Brown on the phone saying, "No, I think he's

writing." In the next panel, Snoopy is shown on his dog

house, pecking on a typewriter. "Dear Friends...," it

reads.

The final panel, decorated with images from the strip, is

Schulz's farewell.

"Dear Friends, I have been fortunate to draw Charlie

Brown and his friends for almost 50 years. It has been

the fulfillment of my childhood ambition.

"Unfortunately, I am no longer able to maintain the

schedule demanded by a daily comic strip. My family

does not wish Peanuts to be continued by anyone else,

therefore I am announcing my retirement.

"I have been grateful over the years for the loyalty of our

editors and the wonderful support and love expressed to

me by fans of the comic strip.

"Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Linus, Lucy ... how can I ever

forget them ..."

The letter ends with Schulz's signature.

Classic "Peanuts" images decorate the letter: Lucy

pulling away a football as Charlie Brown tries to kick it,

Snoopy trying to steal Linus' blanket, and Lucy getting

hit on the head by a baseball with a loud "Bonk!"

Schulz's contract stipulates that no one else will ever

draw the strip, which debuted Oct. 2, 1950, and reached

an estimated 355 million readers daily in 75 countries.

United Feature Syndicate will continue to publish

"Peanuts" reprints.

Good Grief: Peanuts fans reflect on last Sunday strip

Sunday, February 13

By Mary Ann Lickteig

Associated Press

SAN FRANCISCO -- This is the sort of situation Charlie Brown would find himself in: writing to his hero, searching for just the right words to explain how much the man has meant to him and trying to say thank you.

Feverishly, he would work, tongue planted in the corner of his mouth, elbows on the table, pen blotting and smearing. Wadded-up, rejected drafts would rise behind him. Mount Inhibition.

This is the challenge fans face with the retirement of "Peanuts" creator Charles Schulz and the end of the most widely syndicated comic strip in history. The final new strip runs Sunday.

Readers can't believe they won't see Charlie Brown swoon for the Little Red-Haired Girl again or hear Lucy dispense advice from her psychiatrist stand. But how do they tell Schulz how they feel?

Gulp.

"I have loved that round-headed kid since I was 4 years old," says Justin Gage of Hampstead, N.H. "And with all the practice in the world, I honestly, still, at 31, can't keep my kite out of the trees in my backyard."

Schulz's characters showed up on people's doorsteps every single day for nearly 50 years. They brought distinct personalities, hopes, fears and foibles. Schroeder carted a toy piano. Linus brought his blue blanket. And people took them in.

Julian McCarthy, a 43-year-old engineer from Kingston-upon-Thames, England, says "Peanuts" characters make you happy but also "contact your conscience and make you reflect on a course of action, something maybe you've said or done."

They'll be lifelong friends, he says, even though Schulz's contract stipulates that no one else will draw the strip again.

In December, shortly after he was diagnosed with colon cancer and suffered a series of small strokes during abdominal surgery, the 77-year-old cartoonist decided his deadlines had become too rigorous. It was time to stop.

His daily strips ran out last month. United Feature Syndicate will continue offering old panels for comics pages.

Fellow cartoonists have penned tributes. "AACK! I can't stand it!!" Cathy shouted as she read the last new daily "Peanuts" strip.

And ordinary fans, from coffee shops to the White House, are trying to express their gratitude and explain what the strip has meant to them, writing to newspapers and sending sentiments into cyberspace.

A hundred letters a day arrive at Schulz's studio, located at 1 Snoopy Place in Santa Rosa -- down from the 500 per day that arrived for several weeks.

Schulz stopped by and saw boxes of them in the conference room. "What is all this?" he asked secretary Edna Poehner.

"Your love letters," she said.

"All I did was draw pictures," he said.

No, the letter writers say; he changed lives. Since Schulz announced his retirement, a lot of flesh-and-blood people admit they have been crying, grieving for a troupe of two-dimensional children, a superior beagle and a plucky little bird.

"I know it is just ink on a page," says 25-year-old Adam Smith of Hoover, Ala., "but to those of us who loved them, the gang is very, very, real."

Mari Pappas credits them with shepherding her to adulthood. "Without going into detail, my childhood could best be termed 'lousy' by just about anyone's standards," the 38-year-old Reston, Va., woman says. "But faith in God plus the incredible humor, tremendous art and wise counsel of the 'Peanuts' gang pulled me through difficult moment after difficult moment."

Pappas watched "Peanuts" characters wrestle with insecurities and failures. They dealt with their struggles in a sophisticated manner, she says. "It made me realize that I was not alone in having problems that were of a serious nature."

In his characters, Schulz gave us enough detail to recognize personality types but little enough so that we could still see ourselves in them, says Boston College sociology professor Paul Schervish. "We so identify with them because they are not presented as free from dilemma," he says. "That's why it's so powerful ... because that's our life."

Sharona Elfus-Schatzkin met Frieda and learned that she could be beautiful. "I grew up in the era of long straight hair and bell bottoms pants," the Rohnert Park, Calif., woman says. "I wanted straight hair so bad I would torture myself with large orange juice cans and an iron to create the illusion that my hair was as straight as a board. ... Then along came Frieda, who was so proud of her naturally curly hair."

Charlie Brown's cerebral sidekick, Linus, is the most intellectual yet most innocent member of the cast. "How many cartoon characters who are little kids can quote Bible scripture without batting an eye and believe in something like the Great Pumpkin at the same time?" asks Susan Namath of Palm Harbor, Fla.

Lucy's little brother may have needed a security blanket, but he rarely doubted his convictions, says Adam Smith. "Linus taught us that our beliefs are our own. No one can or should tell us what to believe." Smith clung to that conviction as a psychology student when his classmates trumpeted their atheistic views, challenging his belief in God.

"Peanuts" helped Louis Arata get through school, too. While Peppermint Patty struggled Ï "Mark the spot where you last saw me. Mark the spot where I drown in a sea of `D minuses' and `incompletes,' " she said -- "Peanuts" helped Arata pass a college course called "The Bible as Literature."

"So many times during tests, I could recall what book a quotation was from because I could relate it back to a comic strip," he says. He is 35 now, and the director of admissions in the humanities division at the University of Chicago.

The Rev. Robert Short of Monticello, Ark., has lectured for 35 years about the theological implications of "Peanuts."

"The best way to look at the strip, from my perspective, is that it frequently is like the parables in the New Testament," he says.

Schulz's first "Peanuts" strip was published in seven newspapers on Oct. 2, 1950.

It showed Shermy and Patty sitting on a curb watching Charlie Brown approach. "Well! Here comes ol' Charlie Brown!" Shermy says. "Good ol' Charlie Brown ... Yes, sir! ... Good ol' Charlie Brown. ... How I hate him!"

Schulz has said he regrets using the harsh punch line, but he introduced an unforgettable character.

No one knew it then, but the day Charlie Brown walked onto that page, he embarked on 50 years of failed attempts, foiled hopes and near misses. And yet, week after week, he walked back onto the page.

His angst mirrored his creator's. When he was a high school senior, Schulz submitted drawings for the school yearbook, and they were rejected. Twenty-five years later, when his classmates planned a reunion, Schulz was on the "whatever happened to" list.

Even now, with a strip published in more than 2,600 newspapers in 75 countries, Schulz, a man who says "Good grief" in real life, wishes he was "a better drawer." He doesn't seem to believe his success.

How much proof does he need?

His name is in the dictionary (The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language). National Cartoonists Society president Daryl Cagle considers him the most successful artist in history. The Rev. Short says his characters often speak the word of God. In a tribute to Schulz, President Clinton said Charlie Brown and his friends "taught us all a little more about what makes us human."

Still, Schulz doesn't believe. He is mystified by the reaction to his retirement. "It is amazing that they ... think that what I do was good," he has said.

Peter Sledzianowski believes. The second-grader from Simpsonville, S.C., wrote to Schulz: "I like your comic strips. They air (sic) very funny. You draw well."

You draw well. If you can believe anyone, Mr. Schulz, you -- the cartoonist who muted adults and let children speak truths -- can believe Peter.

The boy's voice joins thousands. People around the world want you to know they like your work. Can't you see them, standing shoulder-to-shoulder-to-shoulder ringing the globe? Heads back, noses pointed to the sky, mouths open. Above them floats a giant dialogue balloon holding words penned in capital letters, "YOU'RE A GOOD CARTOONIST, CHARLES SCHULZ!!"

Your strip ends, but your characters live.

There goes ol' Charlie Brown. ... Good ol' Charlie Brown ... How we love him.

Being Charlie Brown

February 13, 2000

By Dan Hulbert

The Atlanta Journal/Constitution

It's enough to make you lie on a doghouse roof and moan, "Why? ... Why?" It's enough to make you sit on a curb and say, "Rats!" It's enough to make you stand all day on a pitcher's mound in the rain after everyone has gone home.

It's enough to make you run for therapy, but you can't -- the crabby girl psychiatrist is "Out," and never coming back.

"Peanuts" is ambling off into the sunset; new strips end today. Charles M. Schulz, 77 and undergoing treatment for colon cancer, is retiring, and no amount of warm-puppy hugs or security-blanket nuzzles will fill this cosmic void.

For a half-century that feels about, oh, six weeks (50 years fly when you're having fun!), "Peanuts" has been a boon to the nation's mental health, providing not only laughter but also a kind of four-panel analyst's couch. For the price of a newspaper we could watch someone else (usually Charlie Brown) endure rejection, mockery, bewilderment and existential angst, sometimes venting it with an "AUGHHHHHHH!" but more often with a gentle "Sigh."

What other comic strip would have the vision, the simplicity, the sheer chutzpah to use "Sigh" as a punchline -- in the '50s, yet? At a time when other strips used slapstick sight gags and heroes with strong jaws and thick blue-black hair, Charlie Brown was way ahead of his time. With no jaw at all, and little hair, he was a postmodern abstraction of Everyboy. He was as alienated as a James Dean character but without a speck of the charisma. He was radically blah. He was so unassertive and round of skull that his friends once used the back of his head to draw a map of the world. He was the chalkboard upon which we projected our disappointments and our fat-chance! dreams of being a baseball hero or being adored by the little red-haired girl.

Yet this pieface martyr had to find strength within himself, for when he sought help with "psychiatrist" Lucy, she said, "Get over it. Five cents, please."

Schulz was angry when one commentator called Charlie Brown a loser, because, he said, "How can you say that when he never stops trying?"

Snoopy as swami

It was just as therapeutic to see Snoopy breeze through life. He was ying to Charlie Brown's yang, as liberated from cares as his owner was lumbered by them. Snoopy didn't sit around moaning about fantasies -- he lived them, as hipster, novelist, Legionnaire, surfer, golfer, vulture, World War I Flying Ace. Talk about evolution: an ordinary beagle during the 1950s, Snoopy in 1960 stood upright and became a biped. He stopped sleeping indoors and instead, like a swami on his bed of nails, took to balancing trancelike on the peak of the doghouse roof. So free was Snoopy that, when the spirit of the Flying Ace was in him, his doghouse lifted off the ground and streaked over the skies of "Europe."

Pretty mind-bending stuff for a sweet little family comic strip.

Like St. Francis of Assisi, Snoopy was joyful enough to talk to the birds. One of them -- that bohemian-looking, fluffy-top Woodstock -- told Snoopy that his philosophy was "Small is beautiful."

Yes, "Peanuts" was square -- proudly square -- but in its own, slightly offbeat, Zen-like way.

Look at any other strip running when "Peanuts" started in 1950, and it looks like a dinosaur, frozen in time. Cartoonist Al Capp took pot shots at "Peanuts" for its neuroses in his "Lil' Abner" strip, but Schulz -- as "Abner" fades in collective consciousness -- has the last laugh. "Peanuts," with its spare, shapely design, still fits on a Third Millennium funnies page, displaying the classic, timeless line of a Coke bottle or a 1965 Mustang. In the words of Patrick McDonnell, Schulz's friend and fellow cartoonist ("Mutts"), " `Peanuts' is so well drawn that you always know what those kids are thinking behind those little ink-dot eyes. `Peanuts' was always on top of it."

At a time when Little Orphan Annie had zeroes for eyes, Lucy had worry lines around hers. There was something almost Samuel Beckett-ish in the absurdist mini-plays involving Spike, Snoopy's lonely brother in the desert; the Great Pumpkin, like Godot, never comes. The "Peanuts" kids may live in a generic, All-American suburb, like Dennis the Menace, but its undercurrents of philosophical questioning and atomic-age anxiety came straight from the Left Bank.

A force for education

"Peanuts" had no adults and didn't need them because the kids' speech was so grown-up. Schulz made literacy cool and so was a force for education. The Minnesota native's drawings were so charming that he made kids want to read better, to understand the jokes about Tolstoy and the Book of Job and "Citizen Kane." (Remember how Lucy spoiled the movie for Linus, telling him, "Rosebud's the sled" and causing him to scream "AUGHHHHHHHH!" in anguish?)

Steve Jones of Sylvania, Ala., wrote in an e-mail to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, "Charlie Brown, when I was a little boy, you alone drew me into the world of books. Thanks for helping raise us all."

It wasn't just the adult in the kid that made "Peanuts" a lifelong habit for many of us, it was the kid that never left the adult. Schulz embraced his inner child long before it became a buzz phrase. There is a lot of Charlie Brown in Charlie Schulz -- beginning with the fact that they both had salt-of-the-earth, barber dads. Journal-Constitution columnist Rheta Grimsley Johnson wrote in her 1989 biography, "Good Grief : The Story of Charles M. Schulz," that the cartoonist's loneliness dates back to his mother's untimely death -- a "grief that he kept fingering like a rosary."

In Schulz's life there really was a crabby little girl -- his first daughter, Meredith, the model for Lucy, and it was she who banged on the toy piano that turned up under Schroeder's precocious hands. There really was a weird year of Schulz's boyhood in Needles, Calif., the same barren setting for Spike and the talking cacti. There really was a little red-haired girl (now a white-haired Minnesota housewife) who broke Schulz's heart and got engaged to another guy just when 20-year-old Sparky was about to pop the question.

"Sparky feels those defeats as if they happened yesterday," Johnson said recently, "examines them as if they were day-old wounds."

There were fewer surprises, no major new characters, as the strip headed into its final 25 years; younger generations seem not to have embraced it like us baby boomers. Yet the wit never lost its edge. Johnson declares: "The strip never grew stale or fell out of style because it was never `stylish' to begin with."

Many faces of the dreamer

There's a theory that in dreams, all characters are aspects of the dreamer. Schulz has confessed how each "Peanuts" character is a thread of himself -- including Lucy, when he's in one of his bitter moods. Perhaps that's where the strip gets its dreamlike quality, the sense that we're seeing the many layers of one lively psyche being revealed, within an ironically ordinary, "normal" suburban setting.

One senses, too, special closeness between Linus and his creator. Perhaps it's because of the lovable absurdity of a pint-sized scholar who can quote Scripture (Schulz was a devout member of the Church of God as a young man) yet drags a ratty blanket around all day. Hence the term security blanket, invented by Schulz. The cartoonist knows well that under our grown-up costumes, no matter how big our job titles or mutual funds may be, there will always beat the heart of a needy tyke.

Schulz writes in "Peanuts: A Golden Celebration" that in first grade, everyone was assigned to make a valentine for another student; not wanting to hurt anybody's feelings, he made one for everyone. Then he got so self-conscious about stuffing them all into a box in front of the class that he failed to deliver any.

Now consider the strip in which Charlie Brown tries to steal home and slides! ... but comes to rest in a cloud of dust only halfway down the base line, blowing the game. Night falls. We see Charlie Brown, still lying on his back, crying, "Why? ... Why?"

Linus is sent out in his pajamas to ask him to lower his voice so everyone can sleep. The last panel is Charlie Brown saying in a tiny voice, "Why?"

Below the black comedy of that scene, there is unspoken tenderness, a sense that, although no one ever bothered to tell him directly, Charlie Brown had a secure place in his world. He was loved.

And so were the "Peanuts" readers. It seems that Charlie Schulz -- in his shy, Charlie Brownish way -- delivered those valentines after all. Every day, for 50 years.

Legendary cartoonist knows human frailty

February 13, 2000

By Rob Rogers

The Post-Gazette

Some kids dream of meeting their favorite movie star. Others dream of meeting their favorite sports hero. I always dreamed of meeting Charles Schulz.

From the time I was 3, drooling on the funnies in the Philadelphia Inquirer, to today's final Sunday strip, "Peanuts" has been an inspiration, a constant companion and a comfort in my life. I would go as far as to say my infatuation with Schulz's round-headed posse led me to become a cartoonist.

Schulz revolutionized the comic strip, not just with his simple and accessible art style, but also with his strong character development. He combined the innocence of childhood with the cynicism of adulthood to create realistic, idiosyncratic and empathetic icons. Each character was put in situations that brought out his or her best humorous possibilities -- Lucy pining for Schroeder, Linus clinging to his security blanket and Charlie Brown, America's most lovable neurotic, always coming up the loser.

I was drawing Charlie Brown and Snoopy before I could walk. My father still blames Schulz for why I didn't go into medicine. I recently came across my little black notebook of cartoon stories drawn when I was about 8. Included were entries such as "Poor Little Snoopy" and "Peanuts in Funny Halloween."

By age 10, I drew Schulz's characters so well that my Dad enlisted me to do illustrations for his medical talks. I became known in pulmonary medicine circles as the kid who drew cartoons of Lucy blowing into a respirator and Snoopy undergoing a bronchoscopy (that's where they stick a bronchoscope down your trachea and look at your lungs.) All of this was done before I had a keen understanding of copyright law. (Please address all legal correspondence to my father.)

My dream of meeting Charles Schulz was realized in 1991 at a meeting of The National Cartoonists Society in Washington, D.C. Every year, the syndicates set aside one night during the convention to take all of their "talent" out to dinner. By chance, my political cartoons are distributed by the same syndicate that distributes "Peanuts." I knew I would be dining with you-know-who. Uh-oh. How would I address him? His good friends call him Sparky, but what would I call him? "It's an honor to meet you Mr. Schulz, Sir, Master, Your Majesty, Your Highness, Your Great Pumpkiness..."

Once seated, I found myself at the opposite end of the table with about 20 other earnest cartoonists in between. After dinner I saw an opening. Schulz was standing on the curb outside the restaurant with no one around. This was my chance! I drew in a big breath and walked toward him. There were so many things I wanted to tell him. How I started drawing cartoons because of him. How I empathized with his characters. How in a business where many comic strips were produced by committee, I admired him as one of the few creators who still wrote and drew the entire strip himself. How I cried the first time I watched the Charlie Brown Christmas special on TV. How he changed my life.

"Mr. Schulz," I said nervously, hand outstretched, "Rob Rogers. I'm a big fan!" As he turned toward me, I could feel the blood rushing to my face and I was thinking, "Big fan!? Did I really just say `big fan'?" He graciously thanked me, grasping my hand. And then it happened. He smiled and looked me right in the eye. I froze. I couldn't speak. The next few seconds felt like an eternity as I stood there gripped with the kind of reverent fear that must accompany one who is standing before God on Judgment Day. His wife finally arrived at his side. He smiled again, letting go of my death grip, and began walking back to the hotel. I felt humiliated. I felt stupid. I felt...like Charlie Brown.

Aaaargh!

As if being tempted to kick the football again, fate offered another chance to be in his presence. In the summer of 1993, I was on vacation in Northern California with my girlfriend. We had driven up the coast and decided to return to San Francisco through Santa Rosa. It dawned on me that Schulz lived in Santa Rosa. Standing at a pay phone in a strip mall, I dialed the number hoping this time I would actually be able to speak. I explained to one of his assistants who I was and that I had met Mr. Schulz on another occasion and that I was in the area desperate for a visitation. It was granted.

As we drove, I felt like a devout Catholic on a spiritual pilgrimage to Rome. I could feel my heart pounding as we entered his studio, more chalet lodge than sterile office. Schulz was warm and generous. Right from the start, he insisted I call him Sparky. This meant a lot to me, especially because addressing him as Your Holiness would have gotten tiresome.

He invited us into his "inner" studio, where we spent almost an hour talking about the state of cartooning and the process of coming up with ideas. He showed us several half-finished cartoons, confiding how he agonizes over every word and ink stroke, pouring his heart and soul into his characters. He recounted sleepless nights worrying he wouldn't be able to come up with any new ideas and described the pain he felt hearing critics say he'd lost "it." He spoke tenderly of unrequited love and how it still affects him some 40 years later. It wasn't hard to make the connection between this sensitive creator and his emotionally complex characters.

Sitting an arm's length away, I finally had the chance to heap some of the life-changing kudos on him that I wasn't able to spit out two years before. He seemed genuinely moved. But coming on the heels of his raw emotions, my words felt weightless and unimportant. I couldn't wait to finish so he could speak again.

Among cartoonists, it's common knowledge that Schulz collects cartoons using "Peanuts" as a metaphor. I described to him a recent political cartoon I had drawn showing Bill Clinton hanging upside down from a tree tangled with several kites. The kites were labeled Whitewater, Travel Office, Nanny-gate, etc. I promised to send it to him. He seemed pleased by this and excused himself from the office. When he came back he was holding an original "Peanuts" cartoon that he proceeded to sign for me. This was better than a personal blessing.

I'm sharing this story simply to give insight into a man whose gift has meant so much to me and to many of you over the past half-century. Charles Schulz, although rightfully revered as cartoon royalty, is a sensitive, sometimes melancholy, hard-working guy who believes in the human spirit. He is, in fact, Charlie Brown. Without Schulz there would be no lovable round-headed kid permanently etched on our collective psyche.

Charlie Brown has always been a mythic hero to me. Whether I was choking on the mound of my Little League baseball diamond, sitting on the C-squad bench in eighth-grade football or too sick to my stomach to call a girl I liked in junior high, I always drew comfort knowing he went before me. He taught me that it's OK to lose. Losing doesn't mean giving up hope. No matter how many times he missed the football, lost the big game or heard Lucy call him a blockhead, Charlie Brown still believed in himself. This is the lesson that helped me get through childhood and now helps me deal with the tangled kite strings of adulthood. This is the gift Charles Schulz has given me.

Thank you, Sparky.

The Peanut Gallery

Hundreds of fans of Charles Schulz's beloved strip gathered in Rice Park to pay homage to a hometown hero, whose last original strip appears today.

February 13, 2000

By Tammy J. Oseid

St. Paul Pioneer Press

Disappointment might set in next week, when avid Peanuts fans open their Sunday newspapers to find reruns of their favorite comic strip.

But Saturday, hundreds of fans of Twin Cities native Charles Schulz attended the "Peanuts" party in St. Paul's Rice Park and were giddy in anticipation of what would happen in today's final original strip.

Burnsville resident Margo Swanson, who grew up with the Peanuts gang, said she would like to see Charlie Brown better Lucy just once. And Swanson hoped that just once, Charlie Brown's unrequited love, the little red-haired girl, would return his affection.