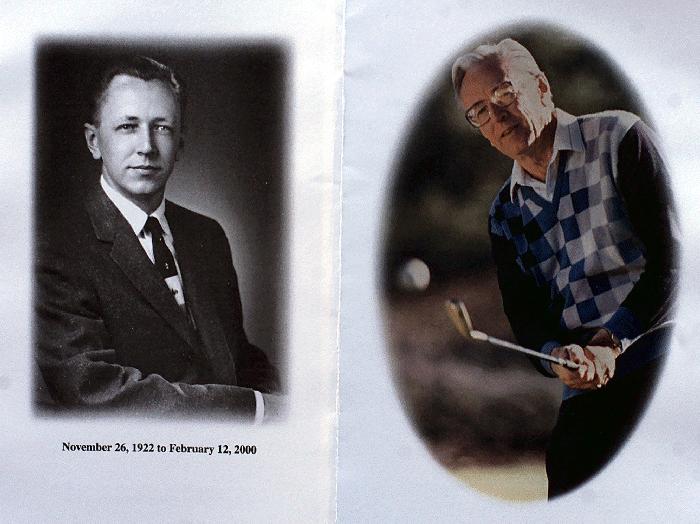

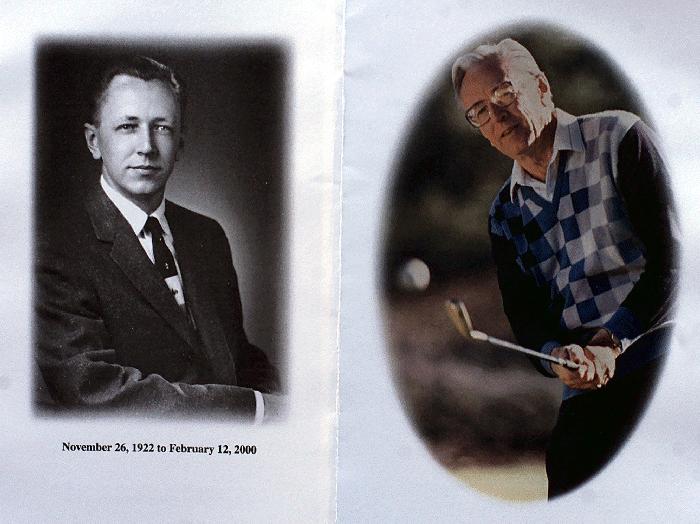

Undated photos of Charles Schulz are seen on the front and back covers of his memorial service program Monday, February 21, 2000, at the Luther Burbank Center for the Arts in Santa Rosa, California. Thousands were on hand to pay last respects to the legendary creator of "Peanuts". (AP photo/Ben Margot)

United in sorrow (page 4)

Friends bid farewell to "Peanuts" creator Charles Schulz

Thousands attend memorial service

February 21, 2000

CNN staff and wire reports

SANTA ROSA, California (CNN) -- About 2,000 friends, neighbors and fans gathered Monday to offer a final goodbye to "Peanuts" cartoonist Charles Schulz.

"You're a good man, Charles `Sparky' Schulz," said tennis great Billie Jean King, one of several who came to offer anecdotes and personal reflections about the creator of the world's most popular comic strip.

Schulz, 77, died in his sleep at his Santa Rosa home on February 12 following a three-month battle with colon cancer.

King, a six-time Wimbledon tennis champion, spoke of her friendship with Schulz.

"It was just fascinating to listen to him. He would ask questions all the time," she said. "We talked about our own insecurities. We talked about how anxious we both were ... As always, he wanted to know what made me win; it was the Lucy in him.

"I said, 'I don't know, Sparky, why do you draw?'

" 'Because I love it. I have a passion for it.'

"I said, 'Touche. That's exactly how I feel about tennis.' "

An overflowing crowd turned out for the memorial service at the Luther Burbank Center for the Arts. Those who couldn't get in watched outside on a large TV screen.

Mourners came from around the block and from around the world to celebrate the life and career of an everyday man who was anything but ordinary. A chorus opened the memorial service singing, "You're A Good Man, Charlie Brown," the title song from a "Peanuts"-based off-Broadway play that debuted in 1967. The service ended with one of pianist Vince Guraldi's upbeat tunes from the ever-popular "Peanuts" television specials.

Widow says Schulz never realized his impact

Schulz's widow, Jeanne, said the world's most widely syndicated cartoonist was a humble artist who never realized how beloved his creations were until after he decided in November that he was too ill to continue the strip.

"He could not know the extent of the impact he had made. I believe that's what these last months have been about," she said. "My comfort comes from knowing that he fully received the love and appreciation that poured out to him."

Schulz, who made more than $30 million a year from the "Peanuts" strip and the many products, videos and licensing deals it generated, was better known in Santa Rosa for giving rather than receiving, both publicly and anonymously.

His money founded or fostered a symphony, community foundation, library, housing development, dogs-for-the-disabled training center and many other projects in the area, as well as the Redwood Empire Ice Arena, where Schulz played hockey.

But still, it was the comic strip that touched the world.

" 'Peanuts' made us realize that our emotions, frustrations, hopes and dreams are common to us all," eulogized Schulz friend Ed Anderson. "And as we pay tribute today to this good and humble man, let us remember that what made Sparky unique was his honesty, the strength of his character and the humor which he brought to his work and to his life."

'Most beloved cartoonist of all time'

Cartoonist Cathy Guisewite, who pens the popular strip "Cathy," said Schulz's death impacted everyone in and out of the comic strip arena. "The world has lost the most beloved cartoonist of all time. The cartoonists of the world have lost our guiding light."

In the week before the memorial service, eldest son Monte Schulz said he saw his father's spirits sag as the artist battled illness and was forced to give up his beloved comic strip.

For the son, it was no coincidence that Schulz died the same weekend his last Sunday strip featuring Snoopy and the gang was published. "He just didn't seem all that willing and interested to fight the colon cancer," Monte Schulz said.

The diagnosis came in November. A month later, the cartoonist announced plans to retire.

In addition to his wife Jeanne and son, Monte, Schulz is survived by another son, Craig; three daughters, Meredith Hodges, Amy Johnson and Jill Schulz Transki; two stepchildren; and 18 grandchildren.

Charlie Brown made debut in 1950

Schulz's final Sunday strip, which appeared on February 13, showed Snoopy at his typewriter and other "Peanuts" regulars along with a "Dear Friends" letter thanking readers for their support.

The last daily strip -- featuring the same farewell message -- had been published on January 3.

Schulz was born in Minneapolis on November 26, 1922, and was raised in St. Paul. He studied art after he saw a "Do you like to draw?" ad. He was drafted into the Army in 1943 and sent to the European theater, although he saw little combat.

After the war, he did lettering for a church comic book, taught art and sold cartoons to the Saturday Evening Post. His first feature, "Li'l Folks," was developed for the St. Paul Pioneer Press in 1947.

Charlie Brown made his debut Oct. 2, 1950, and the tales and travails of the "little round-headed kid" and his gang eventually ran in more than 2,600 newspapers around the world. Snoopy, who made his entrance on the world's stage just two days later, was the only character in Schulz's first farewell strip.

"There are so many things I'm going to miss," Schulz told the Santa Rosa Press-Democrat on January 2. "I've been thinking about this, and I think what I'm going to miss the most is Lucy holding the football and looking up and then the big bonk when Charlie comes down."

Transcript of speech by Cathy Guisewite, creator of "Cathy"

Memorial for Charles M. Schulz,

Santa Rosa, California

It's night. Snoopy bams on the door with his foot. Charlie Brown

gets out of bed, opens the door, and crouches down next to Snoopy on

the porch.

"Are you upset, little friend?" he asks. "Have you been lying awake

worrying? Well, don't worry. I'm here. I'm here to give you

reassurance. Everything is all right. The floodwaters will recede.

The famine will end. The sun will shine tomorrow. And I will always

be here to take care of you. Be reassured."

Snoopy walks back to his doghouse. Charlie Brown gets in bed, pulls

the covers up to his eyes, looks out, and asks, "Who reassures the

reassurer?" [laughter]

The world has lost the most beloved cartoonist of all time. The

cartoonists of the world have lost our guiding light, our god, our

reassurer -- our amazing gentle hero, who made us want to drop to our

knees and worship him. At the same time he made us want to put our

arms around him and tell him everything was OK -- that he wasn't

really that big of a failure [laughter]; that if he'd married the

little red-haired girl, he never would have gotten to meet Jeannie;

that for most people, raising 5 wonderful children, 2 stepchildren,

and 18 grandchildren who were totally devoted to him -- for most

people that would kind of take you out of the "loser" category.

The most inspirational moment of my whole life came the day that I

was spiraling into my weekly creative coma and Sparky called me on

the phone. Of course, it was inspiring enough that he called me,

because I'd never actually even recovered from the fact that Charles

Schulz would speak to me, let alone that he viewed me as being even

in the same profession he was in. But he said, "Hi, this is Sparky.

I can't think of anything today."

And I said "What are you talking about? You're Charles Schulz."

[laughter].

And he said, "I just keep staring at these four miserable blank

boxes. I can't think of anything."

I said, "You're Charles Schulz, you're not me. Of course you can

think of something."

He said, "I'm just like you. I can't think of anything either."

[laughter]

What he did for me that day, he did for millions of people, in

zillions of ways. He gave everyone in the world characters who knew

exactly how all of us felt, who made us feel we were never alone.

And then he gave the cartoonist himself, and he made *us* feel that

*we* were never alone. I think that, in the same way, he never

forgot the exact moment he dropped a ball in a baseball game 69 years

ago. He never really forgot what it felt like to be a new cartoonist

and feel like you're on the brink of global rejection.

So he called us up. He came to our meetings. He looked at our work.

He encouraged us. He commiserated with us. He made us feel he was

exactly like us.

And he was exactly like us -- except for those couple of little

differences.

For instance, Sparky had the exact same deadlines we all do, except

he had no assistants on the comic strip. He had 25 zillion licensed,

products, 40-something animated specials, a TV show, a Saturday

morning TV series, four feature films, a Broadway hit, 1400 books,

part of a theme park, thousands of pieces of mail a week, five

children, two stepchildren, 18 grandchildren to worry about. And

while the rest of the cartoonists stuff down junk food at our drawing

boards, screaming that we can't take the pressure, Sparky always

found time to walk over to the ice arena every day for a nice lunch

[laughter].

While some of us begged for vacations because we were cracking under

the pressure, Sparky worked three months ahead on his comic strip

so he wouldn't have to miss a day when he had heart surgery. While

some of us whine about the shrinking space for our comics in the

newspaper, Sparky was given a smaller space than any cartoonist in

1950, and he created a whole new style of art and writing that was

so eloquent and perfect that every single cartoonist who followed him

has tried to copy something from it.

While some of us insist that we kind of have to push the boundaries

of subject matter to keep our work fresh, Sparky drew a personal code

of ethics for himself, so strict -- stricter than any editor would

have -- and then he brilliantly stayed within his own lines for more

than 18,000 strips.

He worked in handsome slacks and nice sweaters, and he never got

ink all over himself [laughter]. He wrote about doomed romances,

D-minuses, and emotional disaster. And he took the millions of

dollars he *could* have spent on therapy [laughter] and he quietly

gave them away to causes that mattered to him and his family.

He elevated our profession with his dignified, gracious manner.

He raised our standards with his astounding consistency and

commitment. He made us proud of what we do. Everyone in the

room always felt more important when Sparky was in it.

There are cartoonists here from all over the country today. We

were drawn here like members of a family, spread out all over,

who find ourselves desperately needing to reconnect. We need to

see Jeannie, Monty, Jill, Amy, Craig, Meredith, Brooke, and Lisa,

and thank them for giving the man who meant so much to all of us

a real family that he was so proud of, and felt so protected by.

In my last conversation with Sparky a few weeks ago, all he talked

about was how much it meant to him that everyone in his family had

stopped everything they possibly could to be with him when he got

sick.

I remember being with Sparky several years ago at an event where a

group of us was invited to visit with some underprivileged children.

We sat at a long table with paper and markers. And the kids -- all

the kids -- of course immediately hurried past myself and all the

other cartoonists [laughter] to form a line, in front of Sparky.

I remember wondering what it must feel like to know you've touched so

many people in such a profound way that everyone, from grandparents

to tiny children, just wanted something to prove that they'd been in

your presence. I remember watching in awe as the first little boy

came up to Sparky to get his autograph, and Sparky leaned down to

him, and asked the little boy what he'd like him to draw. And I

remember this sweet, shy little face looking up at Sparky and

answering, "Popeye. Can you draw Popeye?" [laughter]

Sparky of course could [laughter]. And somewhere out there, someone

owns a fabulous Popeye signed by Charles Schulz [laughter].

Sparky loved comic strips more than anyone I ever met. He left his

mark on the comic pages forever, not just with the characters he

created, but with the characters created by all of us who were

inspired and encouraged by him, who never even would have done this

for a living if it weren't for him.

Many cartoonists will spend the rest of our lives defining success by

whether or not we think Sparky would like the strip that we just did.

We'll write about insecurities because he paved the way. We'll draw

in simple lines because he taught us how. We'll wail "Aaauugh!" and

"Bleah!" and "Rats!" because he did it first. And like millions of

others, when it all seems so useless and demoralizing, when we're

disgusted and frustrated and out of hope, we'll sit quietly, look a

Peanuts comic strip, and receive Sparky's eternal gift to all of us.

We'll feel reassured.

BBC News Online: World: Letter From America

February 21, 2000

Charles Schulz: a great and good man

A great man has died, probably the greatest American humorist since Mark Twain.

More than that, when a whole wall of the Louvre was given over to him in 1990, a French curator said: "Why not? He was after all the most famous artist in the

history of the world."

You'll know, in an instant, who I'm talking about if I say that he had 355m readers around the world, appeared in 2,600 newspaper, 75 countries and was

reproduced in 21 languages including three or four that I, supposedly at one time a linguistics student, had never heard of.

Charles Schulz is the man, the creator, father and protector of an immortal family of 10 kids, two dogs and a bird.

I have a problem in doing what I should most like to do, namely a full blown commemoration as I would do if it were Dickens or Mark Twain who'd died.

I don't know how one can bring alive those simply but beautifully drawn and immediately recognisable children. How to bring them alive to a blind audience?

Normally that's the great advantage of radio over television, a broadcaster - being essentially and nothing but a storyteller - enjoys the luxury of painting his pictures,

the elements and the people of the story, on the imagination of a blind audience.

No distractions, such as bother him if he's telling a story on television. Nobody looking at the storyteller and thinking: "He looks so much older than I'd expected."

Before Charles Schulz, comic strips created or confirmed the regular cliches of family life: the nagging wife, the milk toast husband - remember Casper Milquestoast?

He lasted for years, since timid hypochondriacal milk toast husbands afraid of everything from a mouse to a dentist are universal and have been with us for centuries.

The interfering mother-in-law. And as for children they were either comically untidy or adorable or spunky naughty.

Then quietly with a sad and comic whimper in the late 40s Charles Schulz's frustrated family came into the world.

Many learned men since have called on Freud, Dostoevsky, Dickens to explain it. Umberto Rico was the last one I knew to try. Writing a preface to an Italian

edition of a Schulz book of strips he wrote: "They concentrate in miniature all the neuroses of all the adults everywhere."

Schulz himself was sceptical when it came to large, literary generalisations about his work but he did once say: "Kids have to handle just the same curve balls as

adults. They know it but the adults don't."

Recently he was interviewed on the most serious of our weekly investigative programmes. Most of us wouldn't have recognised him even if we'd been visiting our

stepson in Santa Rosa, California, and he'd walked into the local coffee shop - which he did every morning, seven days a week for years and years, ordering the

same breakfast, then going to his studio and off to work.

The $32m-a-year attributed to him might have been $32,000 for all it affected his plain living and grinding work, seven days a week. On Sunday afternoon he taught

Sunday school.

So there we saw him: a remarkably well-modelled head, a handsome, clean-shaven man, younger looking than 77. A man with glinting glasses and a ready if not

perpetual smile.

He smiled, he said, out of anxiety. Indeed during the same interview he said: "All my stuff comes out of anxiety or melancholy. The characters are me."

Was it Charlie Brown himself who said: "Sometimes I lie awake at night and I ask: 'Why me?' And a voice answers: 'Nothing personal, your name just happened to

come up.' "

And Sally, Charlie's sister, was echoing nobody but her creator when she said: "Daytime is so you can see where you're going. Night time is so you can lie in bed

worrying."

Schulz did that literally, more nights than he cared to count. And what he worried about was nothing but the next situation, the next crisis, what would be the next

identity Snoopy the beagle might want to adopt - a racing pilot, an astronaut - and what to do with Woodstock, the scatterbrained bird they'd adopted.

Hey, why couldn't Woodstock invent bird bath hockey? - Another strip planned. Now he could go to sleep.

Mrs Schulz said that after a while when they were out driving together she gave up asking what he was thinking, she knew he was thinking about nothing but the

family - the strip.

He never took, he refused to take, an idea from anyone else, just as he never hired a helping draughtsman or a writer of dialogue.

Ninety-five cartoonists in 100 do hire a writer to invent their captions. Charles Schulz, throughout 50 years, did everything - every drawing, every idea, ever line of

dialogue of over 18,000 strips.

What moved him over from a great talent to a comic genius was the fact of his own creations - the family: Lucy, Linus, Schroeder, Spike, Snoopy, Marcie, Sally,

Franklin, Pigpen, Peppermint Pattie (the little red-haired girl, by the way, was a transplant from reality: the love of his life who'd turned him down) - the creation of

this family and the thoughts he divined in them and expressed.

We have testimony from 1m children from Japan through every country in Europe that he was their favourite artist if not writer because he knew what they were

thinking and their parents did not.

There are consequently situations and phrases and thoughts that have passed into American idiom - into the folk memory, you might say - and used by many people

who don't know their origin.

Linus, Charlie Brown's pal, always carries a blanket with him, he called it a security blanket - a term which decades ago passed into the vernacular for any protective

device - a savings account, say - any cushion against disaster.

And there are grey-haired men in their 60s who can recite the historic date of November 16th, 1952 - the first time that Lucy held a football at arms length for

Charlie Brown to kick a field goal. Just as he kicked she snatched the ball away.

She's been doing the same thing for 47 years while the decent Charlie Brown hoped one day he might score.

Charlie Brown mooning over the little red girl who ignores him - always the loser.

"Good grief Charlie Brown, what's the matter with you?"

It's gone into the language as the standard complaint of a parent who doesn't, at the moment - or perhaps ever - know what his child is going on about.

When Schulz was asked why the moon-faced, trusting Charlie Brown never won, Mr Schultz exercised - I thought, watching him - great restraint, for he was plainly

talking to an interviewer who didn't seem, at that moment, to have a clue to what Charles Schulz had been all about for the last 50 years.

Gently, with a reassuring chuckle, Mr Schulz said: "Well of course, winning is great but it's not funny and there are no happy endings in my stories because happiness

too isn't funny."

That's a remark that goes deep, I think, into a vein - perhaps the nerve end - of all great, as distinct from jolly or talented, humorists.

A deep feeling that the ideal really happens in life. If it seems to, the victor is really a victim who deceives himself. It's true in James Thurber, in Erma Bombeck, in the

best of Dickens.

A happy Woody Allen is an impossibility. Do you remember his response to the great theological question of a quarter of a century ago?

"Mr Allen do you think that God is dead?"

"Not only," he said, "is God dead but you can't get a dentist at the weekend."

The root of sadness, of defeat, is deepest of all in Mark Twain. His readers, a humble mass of ordinary folk, got it from the beginning but the American literary critics

disdained to review such trash. They looked on it - if there'd been such a thing at the time - as comic strip literature.

It took an English critic to call him the American Chaucer - the father of a new native American literature. Bernard Shaw went further, he called Mark Twain the

American Voltaire.

Wrote Mark: "This country can claim to have no distinctive criminal class except, of course, Congress." Everybody roared.

Shaw said: "If his applauding audience knew that he was deadly serious they would lynch him."

So drifting up forever, I believe, from Charles Schulz's grave will be memories of Linus who between thumb suckings thinks of sister Lucy as "the crab grass on the

lawn of life".

Sally Brown whose frequent change of hairdos fails to beguile Linus.

Crabby, bossy Lucy, inspired by Charlie Brown to set up a roadside lemonade stand. Lucy sneering that every kid in America does that: she sets up a psychiatric

stand - a clinic - five cents a cure.

And the debonair beagle Snoopy who sees himself best as a war ace, waving a fist at "curse you Red Baron" till he falls off the doghouse.

And forever, Charlie Brown himself, eagerly looking forward to parties and hearing the greeting: "Here comes good old Charlie Brown" but knowing that his pals

privately call him "blockhead".

A month or two ago when Charles Schulz was diagnosed with a very bad form of cancer he felt his drawing hand failing.

He did a series of strips and he announced that the last one would appear everywhere on Sunday February 13th.

In the middle of the night between Saturday 12th and Sunday 13th, mercifully, he died in his sleep. He was 77.

You're a great and good man Charles Schulz and your family is with us, will stay with us, in Asia and Europe and the Americas and the smallest countries so long as

children and grown ups can see and read, and fail to understand each other.

Schulz memorial draws 2,500

February 21, 2000

By Chris Smith

Santa Rosa Press Democrat

Grey-haired golf buddies and kids clutching Snoopy plush toys joined a crowd of 2,500 at Monday's memorial celebration in Santa Rosa for cartoonist Charles Schulz.

Like the "Peanuts" strips, the public service at Burbank Center for the Arts was both poignant and joyful.

The nearly 2-hour program included tributes and memories from Schulz's wife, Jeannie, and his children, golf pals and friends, among them "Cathy" creator Cathy Guisewite and tennis great Billie Jean King.

"Every single cartoonist who followed him tried to copy something from him," Guisewite told the crowd. She said Sparky Schulz encouraged and befriended the younger cartoonists who idolized him.

"He worked in handsome slacks and nice sweaters and never got ink on hmself," she said. "Everyone in the room always felt more important when Sparky was in it."

Tennis great King thanked Schulz for his many years of support of women's sports. She recalled speaking with him by phone several days before his death.

"He said, `You won't believe it, but I got to ice skate today.'" King said there was a long pause before Schulz added that " `it took two people to help me.' "

A son of Schulz, Monte Schulz, told the assembly, "You've come here to honor my dear father, and I thank you."

He thanked his dad for communicating with the world through the frames of more than 18,000 daily and Sunday comic strips.

"Dad did not draw to earn a living," said daughter Amy Johnson. "He lived to draw."

Following the memorial, the crowd enjoyed Schulz's favorite snack -- chocolate chip cookies and root beer, the beverage favored by Snoopy.

Charles Schulz memorial service

The following is the sequence of the program for the Charles Schulz memorial service, held February 21, 2000, at the Burbank Center in Santa Rosa, California.

A Celebration of Life in Loving Memory of Charles Monroe Schulz

Feb. 21, 2000

Welcome: Ed Anderson

Prayer: John B. Johnson

Hymn: "Softly and Tenderly," Carol Menke, soprano

Jean Schulz

Hymn: "Sweet Hour of Prayer," Stephanie Johnson

Family Remembrances: Meredith Hodges, Amy S. Johnson, Jill Schulz Transki

Video Tribute: Ellen Taaffe Zwilich

Memories of Sparky: Cathy Guisewite, Dr. Robert Albo, Dean James, Charles Bartley, Billie Jean King

Hymn: Faure Requiem "Pie Jesu"

Prayer: Father Gary Lombardi

Reading: Monte Charles Schulz

Prelude: Brahms Intermezzo Opus 118 No. 2

Andante from the Piano Quartet in c minor, Opus 60

Kay Stern, violin; Meg Eldridge, viola; Robin Bennell, cello; Norma Brown, piano

Special musical selections, David Benoit, piano

Immediately following the service, please join us outside for the "Missing Man Formation" fly-by.

"Peanuts" Creator Honored in California

February 21, 2000

By Mary Ann Lickteig

The Associated Press

SANTA ROSA, California -- Tennis great Billie Jean King, cartoonist Cathy Guisewite and other fans of Charles Schulz remembered the "Peanuts" creator Monday as a humble genius who never realized until his dying days how much the world loved him.

The timing of Schulz's death from colon cancer nine days ago, just as his final strip was being published, was no coincidence, said Amy Johnson, one of his five children.

"He was taken from this world to the next at the most sacred of moments for him because he earned it," she told the audience of more than 2,000, which filled an arts center in the town where Schulz lived for 27 of his 77 years.

Schulz's widow, Jean, said the world's most widely syndicated cartoonist was a humble artist who never realized how beloved his creations were until after his cancer diagnosis in November and decision to retire that followed.

"He could not know the extent of the impact he had made. I believe that's what these last months have been about," she said. "My comfort comes from knowing that he fully received the love and appreciation that poured out to him."

Schulz, who made more than $30 million a year from the "Peanuts" strip and the many products, videos and licensing deals it generated, is better known in town for giving than receiving, both publicly and anonymously.

His money founded or fostered a symphony, community foundation, library, housing development, dogs-for-the-disabled training center and many other projects in the area, as well as the Redwood Empire Ice Arena where Schulz played hockey.

"He was just a good man," said Doug Lightfoot, a retired pharmacist who recalled how Schulz let his wife's troop of campfire girls skate for free. "He was always very supportive of the community."

Guisewite, who draws the comic strip "Cathy," said Schulz sought her out from time to time. One day, he called her when he couldn't think of anything to draw.

"I said `What are you talking about, you're Charles Schulz!"' she said, recalling how reassuring it felt to know that even the greatest struggle sometimes.

"What he did for me that day he did for millions of people in zillions of ways," Guisewite said. "He gave everyone in the world characters who knew exactly how we felt."

King, who helped Schulz raise money for youth grants by playing at the Snoopy Cup, a senior tennis circuit match at the ice rink, wore a Snoopy lapel pin as she recalled how Schulz sought her out at a match and invited her to Santa Rosa.

What he really wanted to know, she said, was what made her compete.

"He would probe and probe and probe, ask questions all the time. We talked about our own insecurities, which are many. We talked about how anxious we both are," King said. "It was the Lucy in him, asking me. A little psychology here."

After the ceremony, the crowd was fed chocolate chip cookies and root beer -- standard fare for the "Peanuts gang." British World War II-era fighter planes flew over in a missing man formation, the middle plane trailing smoke from its wings.

Schulz was buried in nearby Sebastopol after a private funeral last week.

Thousands Mourn "Peanuts" Creator Charles Schulz

February 21, 2000

Reuters

SANTA ROSA, California -- A costumed Snoopy on Monday welcomed more than 2,000 mourners, some clutching stuffed dolls of "Peanuts" characters, to a farewell for the late cartoonist Charles M. Schulz in his California hometown of Santa Rosa.

Family and friends of Schulz, who died Feb. 12 at age 77, remembered the cartoonist as a humble man who would have been surprised at the outpouring of affection that followed his death after a three-month battle against colon cancer.

"It's a wonderful thing to know that my dad touched the lives of so many people," said Schulz's daughter, Meredith Hodges. "It always surprised dad when people wanted to talk to him."

Buses began dropping people off at the Luther Burbank Center for the arts in Santa Rosa, about 50 miles north of San Francisco, several hours before the ceremony began. So many attended that organizers had to send the overflow to a parking lot, where the service was shown on a giant TV screen.

Surrounded by bouquets of flowers, speakers including tennis great Billie Jean King reflected on the life of the Minnesota-born barber's son who created the comic strip read by an estimated 350 million fans in 75 countries.

The 90-minute ceremony ended with three World War II-era planes buzzing the auditorium in the "missing man" formation. Snoopy spent much of the 50-year life of the strip fantasizing about battling the Red Baron from atop his doghouse.

"Peanuts made us realize that our emotions, frustrations, our hopes and dreams were common to us all," said Schulz's longtime friend Ed Anderson.

Cathy Guisewite, who draws the strip "Cathy", said cartoonists looked up to Schulz -- nicknamed "Sparky" after a character in the Barney Google comic strip -- not just because he revolutionized comic pages but also because he was willing to help those just getting started in the business.

She recounted how she had become frustrated one day because she did not know what to draw. Schulz cheered her when he phoned to say that he, too, had been staring at a blank page.

"He never really forgot what it was like to be a new cartoonist," Guisewite said. "The world has lost the most beloved cartoonist of all time and the cartoonists of the world have lost their guiding light."

Even though a series of strokes had weakened Schulz and left him unable to draw, his death on the eve of publication of his final strip still came as a shock.

But daughter Hodges said it was a fitting end for a man who created the characters -- like lovable loser Charlie Brown -- who faced the same pitfalls and triumphs as the millions who read his strip.

"In a way, it was a miracle," she said. "How appropriate that when ("Peanuts") ended so did he."

Schulz, whose primitive drawing style was criticized in the early years of the strip, was estimated to have made about $55 million. The Peanuts gang was featured in TV specials and advertising campaigns and spawned a Broadway show.

Many who attended the memorial came out of respect for Schulz and his generosity in the town some 50 miles north of San Francisco.

He and his wife Jean pledged $5 million for a high tech information center at a local university and the cartoonist, who played hockey into his 70s, built an ice rink so all the town's children could learn to skate.

"We wouldn't have hockey in Santa Rosa if it weren't for Charles Schulz," said Jim Wentworth, who came to the service with his 16-year-old son. "It (the rink) was never run as a business, it was run as part of his home."

Others, like 10-year-old Taylor Wall, said they were there because they were simply fans. "I came because I like Snoopy and Woodstock," Wall said. "It's good that so many people remember him."

"Peanuts" creator honored in his adopted hometown

February 22, 2000

By Mary Ann Lickteig

The Associated Press

SANTA ROSA, California -- After weeks of tributes revealing what "Peanuts" creator Charles Schulz has meant to fans around the world, those closest to him spoke Monday at a public memorial, celebrating the humble genius they called "Dad" or "Sparky."

His children -- Meredith Hodges, Monte Schulz, Craig Schulz, Amy Johnson and Jill Schulz Transki -- said the world's most widely syndicated cartoonist would always put down his pen to come out for a baseball game.

"I didn't even know my dad had a job," Transki said. When school forms asked for parents' occupations, Transki said she used to think, "They call him a cartoonist, but that's embarrassing; I don't want to put that. I wish he was a banker or something real."

Schulz, who had colon cancer, died 10 days ago, the night before his final comic strip was published. About 4,000 people came to celebrate him at an arts center here in the town he called home for 27 of his 77 years.

Several locals said they had never met the famously low-profile celebrity, but they knew that he quietly supported a symphony, community foundation, library, housing development, dogs-for-the-disabled training center and many other projects, including the Redwood Empire Ice Arena, where he played hockey.

Retired pharmacist Doug Lightfoot said his wife used to bring her Camp Fire Girls troop to the arena and Schulz let them skate for free.

"He was just a good man," Lightfoot said.

"Cathy" cartoonist Cathy Guisewite recalled the day she picked up the phone and Schulz told her he couldn't think of anything to draw.

"I said, `What are you talking about? You're Charles Schulz!' ... He said, `I'm just like you. I can't think of anything, either,' " she said.

"What he did for me that day, he did for millions of people in zillions of ways," Guisewite said. "He gave everyone in the world characters who knew exactly how we felt."

Tennis great Billie Jean King wore a Snoopy lapel pin and shared the topics of conversations she had with Schulz. He wanted to know how she won, and what made her compete.

"He would probe and probe and probe, ask questions all the time. We talked about our own insecurities, which are many. We talked about how anxious we both are," King said. "It was the Lucy in him, asking me. A little psychology here."

Schulz's widow, Jean, said her husband didn't expect the overwhelming reactions that came after he decided in December that he was too ill to continue the strip.

"He could not know the extent of the impact he had made. I believe that's what these last months have been about," she said. "My comfort comes from knowing that he fully received the love and appreciation that poured out to him."

After the ceremony, the crowd was fed chocolate chip cookies and root beer -- standard fare for the "Peanuts gang." Three British World War II-era fighter planes flew over in a missing man formation, the middle plane trailing smoke from its wings.

Schulz, who was buried in nearby Sebastopol after a private funeral last week, leaves behind his widow, five children, two stepchildren and 18 grandchildren.

Sundays Will Never Be the Same

Fans Mourn the Passing of Charles Schulz

February 22, 2000

By Dave Astor

Editor & Publisher Magazine

Charles "Sparky" Schulz died Feb. 12, but he got to see his last Sunday strip as it appeared in the Feb. 13 Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

One of his staffers, former J-C graphics editor Paige Braddock, showed him the preprinted comics section Feb. 9. As Schulz looked at the panels -- including Snoopy pulling Linus by his security blanket and Lucy yanking the football away from Charlie Brown -- he told Braddock in his modest but proud way: "I drew some funny things."

The Santa Rosa, California-based creator also had a funny (as in eerie) sense of timing: He died in his sleep less than three hours before the date of his last original Sunday "Peanuts." Indeed, it was already past midnight in New York, home of United Feature Syndicate.

"It's just the ultimate twist to the story," says Amy Lago, United's executive editor of comic art. "Sparky would appreciate that more than anyone else. He loved a good story."

The "Peanuts" story began on Oct. 2, 1950, when United launched the strip in only seven newspapers. But Schulz's creation eventually became the most widely syndicated comic in history, with 2,600-plus newspaper clients and an estimated 355 million readers in 75 countries. Even after the last original daily strip appeared Jan. 3, more than 90 percent of clients opted to use reruns -- which will continue for the foreseeable future.

While the reruns are helping many readers adjust to the end of "Peanuts," the youngest of Schulz's five children says the cartoonist had a hard time adjusting to life away from his drawing board. "He could do other things, but there was nothing that instilled that same passion to get up in the morning," Jill Transki tells E&P Online.

Schulz, 77, was forced to retire because of serious health problems. He succumbed to colon cancer, according to his death certificate, but some media reports said a heart attack might have killed him. In the weeks before his death, the cartoonist felt better some days than others, and even managed to ice skate a little with one of his grandchildren on Feb. 11.

Transki says her father took solace from the massive, glowing media coverage sparked by his retirement and the thousands of get-well cards that overflowed his office.

Obviously, millions of people loved the extraordinarily multidimensional "Peanuts." It was simply drawn but psychologically complex, funny but melancholy, secular yet religious, and grounded in reality while capable of soaring flights of Snoopyesque fancy.

Schulz was complex, too: soft-spoken and humble, yet very confident in his work. "Deep down, he definitely knew how good he was," says Transki, adding that her father was especially proud that his fame resulted from hard work.

Indeed, Schulz thought up, drew, lettered, and inked every "Peanuts" strip -- more than 17,000 -- over nearly a half century. Once in a very great while he used an idea inspired by his children, such as when Transki wondered if people clasping their hands upside down got the opposite of what they prayed for.

Schulz was also reliable and meticulous. "Working with Sparky was absolutely the best because he was such a consummate professional," says Lago. "He was always on time or early, and he never had a misspelling the first three or four years I worked for United."

Over the years, Schulz was also heavily involved with more than 50 "Peanuts" TV specials, 1,400 "Peanuts" books, scads of licensed products, and other spinoffs that helped make him a millionaire many times over. Licensing will continue.

And Schulz spent countless hours helping and encouraging younger cartoonists -- talking with them over the phone, inviting them to Santa Rosa, and writing scores of forewords for their comic collections.

"Stone Soup" creator Jan Eliot of Universal Press Syndicate recalls that Schulz gave her advice when her comic's client list plateaued at one point. "He told me that `Peanuts' was only in about 45 papers for five years, and he was going crazy," Eliot says. "The thing that made the difference, finally, was when he had Snoopy stand up and have thoughts. He encouraged me to try to think of the unique thing I could do."

"Luann" creator Greg Evans, now with United, recalls nervously meeting Schulz for the first time at the 1985 Newspaper Features Council conference in San Francisco. Schulz made Evans feel comfortable by inviting him to lunch.

"Curtis" creator Ray Billingsley of King Features Syndicate frequently talked and consulted with Schulz. "I looked up to him a lot," he explains. "It was almost like a father-son relationship."

Lynn Johnston, creator of United's "For Better or For Worse," was also close to Schulz. Indeed, she penned a tribute to him in the Oct. 30, 1999 E&P issue which named Schulz -- along with William Randolph Hearst, Walter Lippmann, Joseph Pulitzer, Ernie Pyle, and others -- one of the 25 most influential newspaper people of the 20th century. Johnston wrote that "Peanuts" had "an honesty that healed even when it hurt."

While Schulz was highly supportive of other cartoonists, he also had a competitive side. When an April 1999 E&P survey found that "Peanuts" and "Garfield" had virtually the same number of newspapers, Schulz insisted his comic had more. Yet the "Peanuts" creator would have loved being a cartoonist even if his strip had been a modest success, according to his daughter.

Greg Evans says Schulz enjoyed talking about the "nitty-gritty" of comics (such as how to structure a gag) with other cartoonists. One venue for this was Schulz's private plane, which the "Peanuts" creator used to ferry fellow artists to National Cartoonists Society (NCS) meetings.

The NCS still plans to give Schulz a lifetime achievement award when it meets in New York May 27. And many cartoonists that day will pay tribute to Schulz in their comics. "It was going to be a secret to surprise Sparky, but we can announce it now," says NCS President Daryl Cagle, whose Web site (http://www.cagle.com) has many "Peanuts" tribute cartoons.

Cagle adds that cartoonists will be asked to donate their May 27 comics to the "Peanuts" museum planned for Santa Rosa. That city was also where a memorial service for Schulz was held Feb. 21, five days after his funeral.

Schulz's family has asked that, in lieu of flowers, contributions be sent in memory of the cartoonist to the National D-Day Memorial Foundation, P.O. Box 77, Bedford, VA 24523. Schulz chaired the foundation's fund-raising campaign, and also helped bring in more than $45,000 for the memorial's $250,000 Bill Mauldin World War II Cartoon Art Gallery Endowment (named after the famed editorial cartoonist).

But what many will remember most about "Peanuts" is its distinctive characters: the hapless but resilient Charlie Brown, the acerbic Lucy, the philosophical Linus, the spirited Snoopy. "They have these really strong personalities," says "Mother Goose & Grimm" creator Mike Peters, of Tribune Media Services. "There's no other strip where you can go down the line and describe each character in one or two words. They were that strong."

And Schulz? "Now that he's gone," says Peters, "you realize, boy, we had a giant in our midst.

Drawing conclusions about Schulz

Fellow Cartoonists Pay Tribute To An Icon

Ray Billingsley, creator, "Curtis," King Features Syndicate: "In a way he hasn't died. His inspiration and creativity will be with us forever. He's an immortal."

Jan Eliot, creator, "Stone Soup," Universal Press Syndicate: "Charles Schulz was a genius of a cartoonist. ... He was one of the first to put so much of himself, and so much of his own feelings, into a strip."

Greg Evans, creator, "Luann," United Feature Syndicate: "I'm going to miss the strip. It was so inspiring to all of us. I always wished I could do something as pure and perfect as `Peanuts' was."

Patrick McDonnell, creator, "Mutts," King Features Syndicate: "He was not only the greatest cartoonist who ever lived but probably the greatest man I ever met."

Mike Peters, creator, "Mother Goose & Grimm," Tribune Media Services: "He wasn't a star, he was a supernova. This guy is going to leave a huge black hole on the comics page."

The last newspaper interview?

It Appears In Ventura County (California) Star

The accessible Charles Schulz gave countless newspaper interviews over the years. Perhaps the last one was conducted Feb. 9 by the Ventura County (California) Star.

Star writer David Montero got Schulz's home phone number from his girlfriend's cousin's husband, who had worked with the "Peanuts" creator. After calling Schulz's office to make sure the ailing cartoonist wasn't feeling too sick to talk, Montero dialed Schulz's number.

"I was nervous," says Montero, 31. "I grew up reading the strip. I even had a "Peanuts" lunchbox. I had this image of him built up from my childhood. What if he turned out to be a jerk? But he was as gracious as I possibly could have imagined."

The 45-minute interview started with Schulz asking where Montero was. He answered "Ventura," but Schulz was actually seeking more specific information. So Montero said he was sitting at his computer, ready to type some notes.

"He said he likes to get a visual idea of what a person on the other end of the line is doing," recalls Montero.

The Star writer says Schulz, who suffered several strokes in recent months, stumbled over some words but gave very cogent, thought-out answers.

During the interview, Schulz discussed matters ranging from the way his World War II experiences built up his self-confidence to the 1970s "Peanuts" reruns now appearing in papers (he thought his work from 1988 on was better).

What did Montero's editor think of all this? Tim Gallagher says he was proud of Montero's enterprise and the way he had numerous questions ready for Schulz. "It's a good lesson," notes Gallagher. "If you do get lucky, you better be prepared."

Montero's story ran Feb. 13. Originally, it was going to coincide with the last original Sunday "Peanuts." As it turned out, it also coincided with the day the Star covered Schulz's death.

"One of a kind...one of the crowd''

E&P's Syndication Writer Remembers Schulz

Since joining Editor & Publisher magazine in 1983, I talked to Charles Schulz about 50 times by phone or in person. He was amazingly accessible and down-to-earth for someone of his stature. And still enthusiastic about "Peanuts" decades after he created the comic.

He would tell me, joyfully rather than boastfully, to look at a great strip he did about D-Day or some other subject. I also recall how much pleasure Schulz took in his art. Indeed, a big reason why he let Charlie Brown hit a home run in 1993 was so he could draw the character doing a magnificent celebratory somersault.

Mixed in with the enthusiasm and gentleness was a man of very strong opinions. I remember Schulz criticizing some creators for using off-color humor or, in the case of some superstar cartoonists, for farming out much of their comic duties to other writers and artists. He also tweaked newspaper editors for running comics too small or not appreciating the craft enough. And Schulz was miffed when people who considered themselves comics fans didn't know much about great strips of the past.

I don't think Schulz criticized any of these people to their faces. He was honest, but also kind.

Perhaps my strongest memory of Schulz dates back to the 1988 National Cartoonists Society meeting in San Francisco. A bus that would transport attendees to the next event was a long time in coming, and some opted to take taxis. Schulz patiently waited for the bus -- not only one of a kind, but one of the crowd.

Breaking News

Just the FAQs, Ma'am

Ace Airlines Tours: Sites to Visit

Beethoven's Rhapsodies: The Music (and Musicians) of Peanuts

Shop Till You Drop

Just for Fun

By Derrick Bang

Legal Matters

All PEANUTS characters pictured are copyrighted © by United Feature Syndicate, Inc. They are used here with permission. They may not be reproduced by any means in any form.